"Many of the artists that are considered so-called Harlem Renaissance artists never lived in Harlem," explains Norwood.

And other prominent contributors aren't originally from there. Case in point: Leslie Garland Bolling.

"His work was shown in the Virginia Fine Arts Museum, the first Black artist shown in the fine arts museum in the 1930s," says Norwood. "It was really only HBCU museums that kept a lot of this art alive."

But in Miami Beach, history buffs and art enthusiasts can see Bolling's piece at a new exhibit at the Wolfsonian-FIU as part of "Silhouettes: Image and Word in the Harlem Renaissance," on view through Saturday, June 23.

"It's a wooden sculpture made with a pocket knife of a bishop of the AME Church, which is arguably one of the oldest Black institutions in this country," says Norwood.

Included in a section dedicated to Black spirituality, it's just one of many items at the event, including more than 35 book covers and interior illustrations and more than 60 sculptures, paintings, photographs, and prints.

And when it comes to Norwood, the exhibit is just the latest in a fervent discussion that he has been having about the Harlem Renaissance.

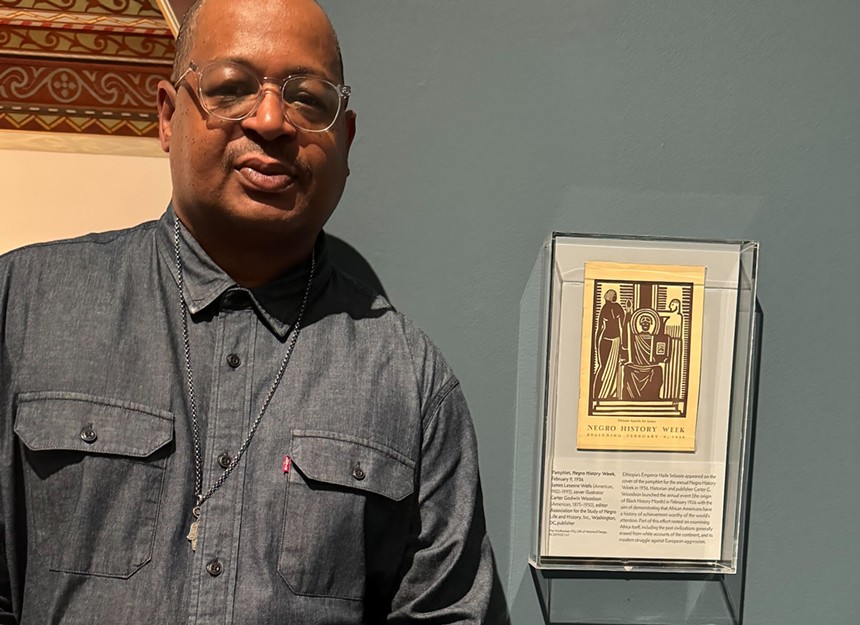

Christopher Norwood curated "Silhouettes: Image and Word in the Harlem Renaissance" at the Wolfsonian-FIU.

Photo by Yvette N. Harris

"I met with them. I looked at their archive of artwork, particularly artwork that reflected Black themes, and I was really pleasantly surprised with what they had," says Norwood.

What he found were photos taken by Carl Van Vechten.

"He's one of the primary patrons of the Harlem Renaissance," explains Norwood. "He also was a photographer. He captured a lot of the intellectuals, entertainers, and artists and documented that period in portraits. [The Wolfsonian] had a small collection of original photos as well."

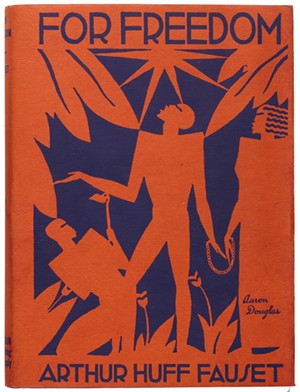

For Freedom, illustrated by Aaron Douglas with interior illustrations by Mabel Betsy Hill

The Wolfsonian-FIU photo

"The covers. The insides. And for me, I was always fascinated by that artwork because Black artists during this time period were not shown in galleries and museums. So their canvas, for many of these artists, were these books. This way, they could actually be seen around the world and around the country."

Ironically, his findings nearly dovetailed with an event that he was hosting himself.

Norwood is the founder and owner of Overtown-based Hampton Art Lovers, a gallery specializing in African-American fine arts.

At the time, he was in the midst of presenting "One Way Ticket: Movement, Migration and Liberty."

The show centers on a book of poetry by Langston Hughes, published in 1949 and illustrated by Jacob Lawrence. It documents the experiences of African Americans who sought to escape oppression by relocating to the North during the Great Migration.

This exchange between Langston and Lawrence, coupled with Norwood's new Wolfsonian findings, sparked a realization that something must be done.

"I was already in this sort of space where I was really impressed by these collaborations," says Norwood. "So when they said they had these collections of books, I was like, Oh, we're going to do a show focused on these illustrations.' And what I'll do is I'll curate artwork from these artists, but we've got to get them from various places."

One of his first steps was to engage historically Black colleges.

"Fortunately, we have one here in Miami. We were able to have work loaned to us from Florida Memorial. We also had work loaned to us from Fisk University in Nashville, which is home of Aaron Douglas, who was the principal artist of that time period [and] the father of Harlem Renaissance art. He taught there for many years. We also had the Aaron Douglas family loan us work directly."

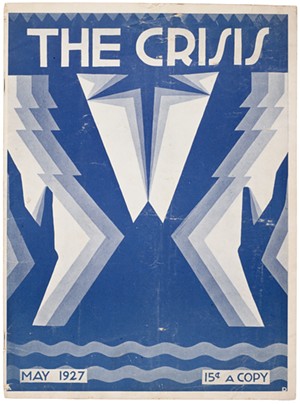

The cover for the Crisis magazine is an iconic example of the artwork produced by Aaron Douglas.

The Wolfsonian-FIU photo

Shawn Christian, an English professor at Florida International University and a staff member at the Wolfsonian, was brought on board to ensure appropriate attribution and placement.

"We recruited Shawn to be the curatorial consultant so that I could really make sure that I'm positioning the importance of these books in their proper context."

For his part, Christian was delighted to be a part of the project.

"Being able to personally go back to the time period that I've been studying for most of my professional life and re-enter it through the arts was really powerful because I'm a literary studies scholar," says Christian. "They were people coming with a different perspective about African American contributions and their role as citizens. And so to tap into that kind of Zeitgeist, in that moment, was really cool."

And like Norwood, he, too, recognizes the beauty of those who used art to celebrate the set of ideals explored in the New Negro movement.

"It's the idea that art can be transformative and socially powerful at this really interesting moment in African American history," says Christian.

He mentions figures like Alain Locke, Aaron Douglas, Jessie Fauset, Zora Neale Hurston, and James Weldon Johnson, who, he says, were encouraged and emboldened to create art and understood the need to preserve what they were doing during such a transformative period.

"And for a lot of these artists, in addition to wanting to make a living and wanting to make great art, they were hopeful that in by doing so, the racial animus of the country would dissipate or just be removed altogether. It was a lofty, ambitious, and arguably crazy goal that in some ways wasn't realized, but [still] they created this body of work that persists and tells its own story, even to this day," says Christian.

– Sergy Odiduro, ArtburstMiami.com

"Silhouettes: Image and Word in the Harlem Renaissance." On view through Sunday, June 23, at the Wolfsonian-FIU, 1001 Washington Ave., Miami Beach; 305-531-1001; wolfsonian.org. Admission is free for Florida residents and museum members; tickets cost $8 to $12. Wednesday through Sunday 10 a.m. to 6 p.m.